11 Least Square Problems and the Normal Equations

11.1 General Setting and Choice of the Approximation

In this chapter, we consider the problem of parameter identification from measured data. Our presentation follows —in a reduced way— the chapter on Least Square problems in Hohmann, Andreas, and Peter Deuflhard. Numerical analysis in modern scientific computing: an introduction. Vol. 43. Springer Science and Business Media, 2003.

We assume that we have \(m\) pairs of measured data \[(t_i,b_i), \;\;\; t_i,b_i\in\mathbb{R}\, \qquad i=1,\ldots,m\, ,\] available. We assume that there is a mapping \(\varphi\colon\mathbb{R}\longrightarrow\mathbb{R},\) such that \[b_i\approx \varphi(t_i)\, \qquad i=1,\ldots,m\, ,\] where the \(b_i\) are interpreted to be perturbed data, e.g. by measurements.

We now would like to find an approximation \({\mathcal N}\colon \mathbb{R}\longrightarrow\mathbb{R}\) to \(\varphi,\) which shall depend on the parameter vector \(x\in\mathbb{R}^n,\) i.e. \[{\mathcal N}(t;x) \approx \varphi(t)\, .\] Obviously, the mapping \(\varphi\) in general can be of arbitrary form. In order to simplify the construction of our model \({\mathcal N}(t;x) ,\) we therefore assume that the model \({\mathcal N}(\cdot;x)\) will depend linearly on the parameters \(x_1,\ldots,x_n\in\mathbb{R}.\) We therefore make the following Ansatz \[\tag{11.1} {\mathcal N}(t;x) = x_1 \cdot a_1(t)+\ldots+ x_n \cdot a_n(t)\] with \(a_i\colon\mathbb{R}\longrightarrow\mathbb{R},\) \(i=1,\ldots,n\) arbitrary functions. Here, we assume that the \(a_i\) are continuous. The choice of the functions \(a_i\) determines implicitly which functions we can approximate well. For example, if we would know that \(\varphi\) is a linear function, i.e. \(\varphi(t)=c_1 +c_2t,\) with \(c_1,c_2\in\mathbb{R}\) arbitrary but fixed, we could choose \(a_1 \equiv 1\) and \(a_2(t)=t.\) Then, \({\mathcal N}(t;x) = x_1 \cdot a_1(t) +x_2 \cdot a_2(t) = x_1 + x_2t\) and we would expect that for the solution \((x_1,x_2)^T\) of the least square system we would have \((x_1,x_2)\approx (c_1,c_2).\) However, in general, \(\varphi\) is unknown and we cannot expect that \(\varphi \in \mathrm{span}\{a_1,\ldots,a_n\}\) as it was the case in our simple example above.

11.2 Least Squares

We now discretize our Ansatz functions \(a_i\) by taking their values at the points \(t_i\) and set \[\tag{11.2} a_{ij} = a_j(t_i)\, \qquad i=1,\ldots,m,\quad j=1,\ldots,n\, .\] Setting \(A=(a_{ij})_{i=1,\ldots,m,\, j=1,\ldots,n}\) and \(b=(b_1,\ldots, b_m)^T,\) we end up with the linear system (\(m>n\)) \[Ax=b\, .\] Here and in the following we will always assume that \(A\) has full rank, i.e. \(\mathrm{rank}(A)=n.\) Since \(A\) cannot be inverted, we decide to minimize the error of our approximation \(Ax\) to \(b.\) More precisely, we see that \[{\mathcal N}(t_i; x) = \sum_{j=1}^n x_j \cdot a_j(t_i) = (Ax)_i\, ,\] and therefore decide to minimize the error \[\tag{11.3} \min_{x\in\mathbb{R}^n} \|Ax-b\|\] of our approximation in a suitable norm \(\|\cdot \|.\) The choice \(\|\cdot\|=\|\cdot\|_2\) leads to \[\|Ax-b\|_2^2 = \sum_{i=1}^m ({\mathcal N}(t_i; x) - b_i)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^m \Delta_i^2 \, ,\] where we have set \(\Delta_i = {\mathcal N}(t_i; x) - b_i.\) Thus, minimizing the error \(\|Ax-b\|_2\) in the Euclidean norm corresponds to minimizing the (sum of the) squared errors \(\Delta_i.\) This motivates the name least squares.

11.3 Normal Equations

Fortunately, the solution of the minimization problem (11.3) can be computed conveniently by solving the so-called normal equations \[\tag{11.4} A^TAx=A^Tb\, .\] We recall that in this chapter we always assume that \(A\) has full rank, i.e. \(\text{rank}(A)=n.\) The derivation of the normal equations (11.4) is closely connected to the concept of orthogonality.

We start our considerations by investigating the set of possible approximations, which is given by the range of \(A\) \[\tag{11.5} R(A) = \{y\,|\,y\in \mathbb{R}^m, y=Ax\}\, .\] We note that from the definition of the matrix-vector multiplication (7.16) that \(R(A)\) is the linear space spanned by the columns of \(A,\) i.e. \[R(A) = \mathrm{span} \{A^1,\ldots,A^n\}\,,\] and we can write the elements \(y\in R(A)\) as linear combinations of the columns of \(A\) \[y\in R(A) \Leftrightarrow y = \sum\limits_{i=1}^n \alpha_i A^i\, ,\qquad \alpha_1,\ldots,\alpha_n\in \mathbb{R}\, .\]

As a candidate for the solution \(x\) of the minimization problem (11.3), with \(\|\cdot\|=\|\cdot\|_2,\) we take the element \(x\in R(A)\) which is characterized by the fact that the corresponding error \(b-Ax\) is orthogonal to \(R(A)\): \[\tag{11.6} \begin{aligned} & \langle Ax-b, y\rangle = 0 \qquad \forall y \in R(A)\\ \Leftrightarrow\quad & \langle Ax-b, Az\rangle = 0 \qquad \forall z \in \mathbb{R}^n\\ \Leftrightarrow\quad & \langle A^T(Ax-b), z\rangle = 0 \qquad \forall z \in \mathbb{R}^n\\ \Leftrightarrow\quad & A^T(Ax-b) = 0 \\ \Leftrightarrow\quad & A^TAx = A^Tb \, . \end{aligned}\] The fact that the error \(b-Ax\) is orthogonal to \(R(A)\) induces also a best approximation property of \(Ax\) of the normal equations (11.4) in the Euclidean norm.

Let \(m>n\) and let \(A\in\mathbb{R}^{m \times n}\) have full rank. Let furthermore \(b\in\mathbb{R}^m\) be given. Then, for the solution \(x\) of the normal equations \(A^T Ax=A^Tb,\) we have the following best approximation property for \(Ax\) in the Euclidean norm \[\tag{11.7} \|Ax-b\|_2 = \min_{z\in R(A)} \|z-b\|_2\, .\]

Proof. We have for \(z\in R(A)\) \[\begin{aligned} \|z - b\|_2^2 & = \|z - Ax + Ax - b\|_2^2\\ & = \|z - Ax\|_2^2 + 2 \langle z-Ax, Ax-b\rangle + \|Ax - b\|_2^2 \\ & = \|z - Ax\|_2^2 + \|Ax - b\|_2^2 \\ & \geq \|Ax - b\|_2^2 \, . \end{aligned}\] Here, we have exploited that, due to \(z-Ax\in R(A)\) and the orthogonality condition (11.6), we have \(\langle z-Ax, Ax-b \rangle = 0.\)

Proof. Exercise.

For later reference, we rewrite this result in a more abstract form

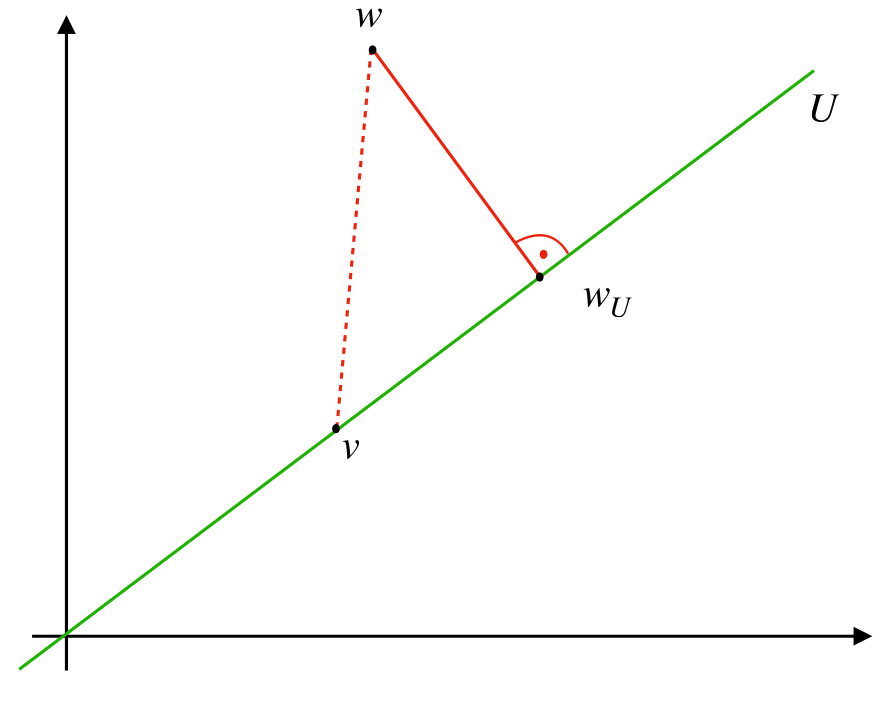

Let \(m\geq n\) and let \(U=\mathrm{span}\{u_1,\ldots,u_n\}\subset \mathbb{R}^m.\) Let furthermore \(w\in\mathbb{R}^m\) and let \(w_U\) be the unique element in \(U\) with \(w - w_U \bot U,\) i.e. \(\langle w-w_U, v\rangle = 0\) for all \(v\in U.\) Then we have \[\tag{11.8} \|w-w_U\|_2 = \min_{v\in U} \|w-v\|_2\, .\]

The proof is literally taken from the above theorem. We repeat it here for notational convenience.

Proof. We have for \(v\in U\) \[\begin{aligned} \|w - v\|_2^2 & = \|w - w_U + w_U - v\|_2^2\\ & = \|w - w_U\|_2^2 + 2 \langle w - w_U, w_U - v\rangle + \| w_U - v\|_2^2 \\ & = \|w - w_U\|_2^2 + \|w_U - v\|_2^2 \\ & \geq \|w - w_U\|_2^2 \, . \end{aligned}\]

We call \(w_U\) the orthogonal projection of \(w\) into \(U\) and refer to Figure 11.1 for a graphical representation.

11.3.0.0.1 Pseudo-Inverse

If \(A\) has full rank, the solution \(x\) of the normal equations (11.4) can be formally written as \[x = (A^TA)^{-1}A^Tb\, .\] This gives rise to the definition of the pseudo-inverse \(A^+\) of \(A\) as \[\tag{11.10} A^+ = (A^TA)^{-1}A^T \, .\] From the definition, we see that \(A^+A = (A^TA)^{-1}A^TA = I_n,\) if \(A\) has full rank. This motivates the name pseudo-inverse.

11.4 Condition Number of the Normal Equations

A straightforward approach for solving the normal equations (11.4) would be to compute \(A^TA\) and \(A^Tb\) and then to apply Cholesky decomposition to the resulting linear system. Although this can be done, in many cases it might not be advisable. The main reason is the condition number of \(A^TA.\)

We recall for our investigations on \(\kappa(A^TA)\) the condition number of a rectangular matrix (8.7), which was defined as \[\kappa(A) = \frac{\max_{\|x\| = 1} \|Ax\|}{\min_{\|x\|=1} \|Ax\|}\, .\] Before proceeding, we show that this definition is compatible with our definition (8.6) for invertible matrices. We first note that the numerator, by definition, is the norm \(\|A\|\) of \(A.\) We continue by investigating the denominator and assume that \(A\in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}\) and that \(A^{-1}\) exists. Then, we have \[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{\min\limits_{\substack{\|x\|=1 \\ x\in\mathbb{R}^n}} \|Ax\|} & = \frac{1}{\min\limits_{0\not = x\in\mathbb{R}^n} \frac{\|Ax\|}{\|x\|}}\\ & = \max\limits_{0\not = x\in\mathbb{R}^n}\frac{1}{\frac{\|Ax\|}{\|x\|}}\\ &= \max\limits_{\substack{0\not = y\in\mathbb{R}^n \\ y=Ax}}\frac{\|A^{-1}y\|}{\|y\|}\\ & =\|A^{-1}\|\\ \end{aligned}\] Putting everything together, we see that for invertible \(A\) we have \[\kappa(A) = \frac{\max_{\|x\| = 1} \|Ax\|}{\min_{\|x\|=1} \|Ax\|} = \|A\| \cdot \|A^{-1}\|\, .\] It now can be shown that the condition number of \(A^TA\) is the square of the condition number of \(A,\) i.e. \[\tag{11.11} \kappa(A^TA) = (\kappa(A))^2\, .\] Thus, in general, it is not advisable to set up \(A^TA\) for solving the normal equations. Instead, as we will see later in the lecture on numerical methods, we will use the so-called \(QR\)-decomposition. The \(QR\)-decomposition is a relative of the \(LU\)-decomposition, which uses orthogonal transformations as elementary transformations.